Enrol in an online course today for flexible, self-paced learning—no fixed schedule required. Plus, enjoy lifetime access to course materials for convenient revisiting.

“How Do I Know Who I Am?” Identifying Existential OCD

One of the less recognised subtypes of OCD is existential OCD. Existential OCD occurs when someone develops pathological doubt about their existence, the nature of their existence or the nature of the existence of others.

For example, a person might watch a science fiction movie and then get stuck wondering if they are stuck in an alternate reality separate from others. Or a person might get stuck obsessing about whether they are dead or alive. They might also obsess about misidentifying their purpose in life, or obsess they are somehow not fully present as a being or not experiencing the right life and somehow got misdirected from a past life or born into the wrong body.

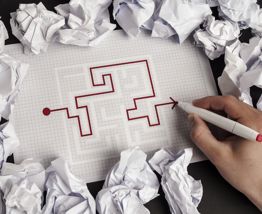

The commonality of existential obsessions and compulsions is the person feels unable to properly verify something about their existence, meaning or purpose and pathological doubt and compulsions designed to eliminate doubt take over.

Patients feel tortured by these ideas and engage in avoidance of anxiety triggers, such as media or conversations about these topics. They may spend hours analysing their experience to detect subtle signs or sensations that might decrease doubt, or seek reassurance by asking questions, reading information on religion, philosophy, or theories of meaning or quantum physics.

For example, someone might scrutinise their body or the reactions of others to verify they are all on the same plane of existence. Unfortunately, they typically misinterpret their symptoms of anxiety, such as depersonalisation or dissociation or feeling fear.

Existential OCD can be confused with:

- psychosis (‘I am trapped in an alternate reality’)

- delusional disorder (‘the odd feeling I get must mean I am trapped in an alternate reality’)

- dissociative phenomenon (‘the odd feeling or dissociation I get when extremely anxious’)

- depersonalisation disorder (‘the feeling of depersonalisation I get when obsessing about whether or not I am stuck in an alternate reality’)

- or body dysmorphic disorder ('I must have been born into the wrong body. What if I am not meant to be in this body?’)

Such confusion is especially likely when symptoms have increased in severity, frequency or if the person attempts to neutralise their obsessions by assuming the worst: “I must be trapped in an alternate reality”, or “I must be dead because I have this dead feeling inside of me.”

The key differences between existential OCD and these other disorders is the person has no other signs of psychosis, such as formal thought disorder, in high likelihood has a family history of mood and anxiety disorders, and is not convinced they are what they fear, but rather is terrified at the idea of “What if it were true?” They are desperately trying to disprove or prevent the awful imagined future by using avoidance, compulsions and reassurance seeking. When they do research on weird topics or phenomenon, they are not true believers, but desperate researchers hoping to prove the absence of a terrible idea.

Effective treatment often includes both medication and cognitive behavioural therapies. Successful treatment teaches the patient how to recognise the ways their pathological doubt tricks them into getting stuck on an endless frightening volley of ‘What ifs?’ that can never be resolved.

Exposure with response prevention and cognitive exercises, designed to help the patient avoid getting sucked in the swirl of ‘What if?s’ helps patients to stop compulsive analysis of their thoughts, sensations and information that OCD takes out of context.

Exposure with response prevention practise helps patients learn to stop reassurance seeking compulsions, avoidance behaviours or other rituals. The most critical part of treatment is helping the patient develop awareness of how OCD hijacks their thinking and behaviour to make the impossible and improbable believable.