Understanding the Pressures on PhD Students

-

-

Rachel E. Morgan

Anxiety and depression are on the rise among PhD students. But therapists working with students aren’t always aware of the very particular pressures clients in this group are under. To mark University Mental Health Day, psychodynamic counsellor Rachel E. Morgan, who works at two university counselling services, shares insights from her practice – and from her own time as a PhD student and postdoctoral researcher.

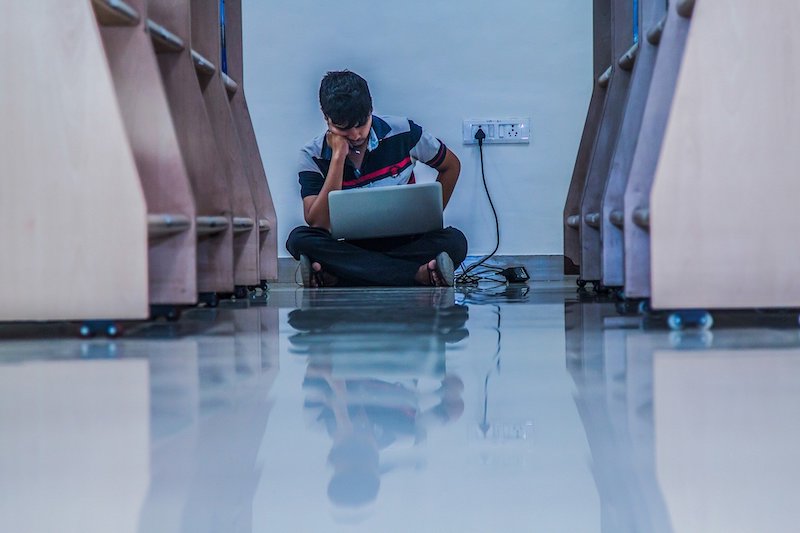

Doing a PhD can be a rewarding thing, but the journey can be difficult and at times feel never-ending. A number of students will reach the end of their PhD and promptly look to leave research. It can be an all-consuming task, and students can feel very isolated with their difficulties and that only they are struggling. However, many of the difficulties encountered are common to the PhD experience.

Recently I went to an event on wellbeing for postgraduate researchers. The comment was made that postgraduate researchers feel they keep having to explain what being a PhD student is like, and the differences to being an undergraduate. So here are some aspects that might be helpful for therapists working with PhD students - particularly those who are laboratory based - to be aware of.

It’s a full time job… plus

PhDs are year round and full time. The culture around PhDs can lead to expectations that students will work extended hours. This can lead to difficulties with work-life balance and burn out. What may feel like the expected pace, is not actually sustainable over the three to four years.

The supervisor / student relationship is key

Often students will feel supervisors are their only port of call, the gatekeeper to their PhD. There are some great supervisors out there. However, there are times when the supervisor / student relationship breaks down. This can leave the student feeling very isolated. Supervisors are academics, who have reached the position they hold because they have achieved excellence in research. They are not necessarily selected on the basis of their management or people skills. They can feel under-skilled to deal with a student who is struggling.

Autonomy is not absolute

Students may start their PhD thinking they have absolute control over the direction of the research. However, when they are under the banner of an academic / principle investigator (PI) – i.e. their supervisor - such supervisors have a vested interest in the direction the research takes. This is particularly true of laboratory based PhDs. This can further complicate the supervisor / student dynamic.

Being unprepared to fail

Students’ previous experience of research / experiments, e.g. in Masters, has often been in the context of projects which are likely to succeed. They tend to be based on research where there is significant experience in the research group. When they embark on a PhD, they enter into the unknown. The whole point is it has not been done before. Failures are not generally published, so it can lead students to feel that they alone are failing.

Second year blues is a thing

This is a real phenomenon. The first year often involves repeating work the group has experience in, to settle the student in. In second year, the student is completely in the unknown. The momentum required to keep up long hours is starting to wane and the idea of sustaining the pace for another one-and-a-half to two years becomes overwhelming. Most students get through this difficult period, and often the majority of data is obtained in the third year.

The time pressure may be intense

Many PhD students are on a time-limited schedule. Most funded PhDs have to be completed – i.e. the thesis submitted – in a four-year time scale. If a student fails to do this (excluding exceptional circumstances) they do not get a PhD and the funding body may be reluctant to fund a student in that academic’s research group again.

The success of research is largely measured in publications and being the first to publish. In this competitve and driven environment, experienceing failure can be felt more keenly. Given that most students come to a PhD having performed well academically, experiencing failure can challenge their sense of who they are. Additionally, being immersed in this environment can mean they lose their sense of who they are outside of the PhD. Providing them space to consider their personal priorities, interests and values can be beneficial. Helping them to challenge thoughts that everyone else is excelling,a nd only they are failing, can help them maintain perspective.

As counsellors, we understand each PhD student’s experience will be unique. But I hope the points above help give an idea of some of the common issues PhD students are dealing with. With the launch of The University Mental Health Charter in December 2019, there is hope that some of these may change, leading to an improved culture around work-life balance and further support for the mental health and wellbeing of students and staff.