Enrol in an online course today for flexible, self-paced learning—no fixed schedule required. Plus, enjoy lifetime access to course materials for convenient revisiting.

The Attachment Paradox

We are social animals, and the social wellbeing of our clients is a crucial aspect of therapy. Over recent years, attachment theory and the neuroscience that supports it have meant that most therapists no longer approach their clients as an island of complex neuroses, but as part of a larger system or systems. As we explore these systems and relationships, we can start to uncover deep wounds, and then begin to facilitate their healing.

Our clients will often speak about experiences that have been painful or traumatising, and which may have led to the unconscious development of certain maladaptive coping strategies and behaviours, and ways of relating to self and others. These experiences may have taken place within our clients’ relationships with parents, loved ones, family, friends, and colleagues. Or they may have been connected to the jobs they do, the money they have, the lives they have constructed, the beliefs they hold, the intergenerational family systems and genetic legacies they were born into – or to themselves and their constituent parts.

Attachment theory can be a helpful guide to framing some of these relationship experiences and their consequences, however it is often presented in a way that can feel confusing or even blaming to clients.

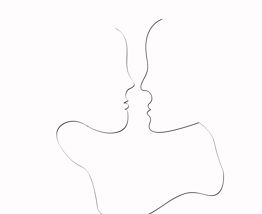

A particularly common problem is how to help clients understand the perfectly natural and predictable cycle of escalation that occurs in bids for connection when a secure attachment relationship feels like it may be under threat – for instance, when there has been a life event which renders an attachment figure suddenly emotionally unreliable.

During these times, a previously secure relationship, or securely attached individual, can quickly fall into anxious patterns. A cycle of escalation occurs, as the anxious and threatened party seeks closeness and reassurance during the time of threat. As seen in Dr Edward Tronick’s Still Face experiment (available on YouTube), this cycle of escalation typically follows the following process:

- Reach (the seeker makes a bid for connection)

- Protest (when this bid is unmet by the giver, there may be a sad or angry protest attempt)

- Despair (as this continues, the seeker falls into a state of despair; often marked by some kind of meltdown or tantrum)

- Detach (ultimately, the seeker turns away and shuts down, going into a state of withdrawal and collapse)

This pattern of pursuit can seem suffocating, needy, or neurotic, and can be quickly matched by a similar pattern of withdrawing and distancing by the other party.

These cycles can seem paradoxical at first, and I often find that clients are reassured when I explain the simple ‘attachment paradox’ to them; that a secure attachment can tolerate distance, whereas an anxious one cannot. This is often a lightbulb moment, as they understand the shift in inter-dependence. They recognise how they were once able to travel separately or have their own individuated friends and interests, whereas now they feel stuck in a pursue and withdraw cycle of enmeshed hyper-vigilance or anxious co-dependence.

These pursue and withdraw cycles, and the painful distance they create, are often what brings clients to therapy, however they are perfectly understandable and reversible. As we identify and understand them, we can quickly de-escalate these maladaptive cycles and then promote new healthy patterns of connection and repair. We can move our clients away from patterns of forced connection and sympathetic arousal, and back into a state of relaxed and connected flow.

An easy way to check for secure attachment is to ask the question, “ARE you there for me?”

- Accessible (can I get to my attachment figure when I need them?)

- Responsive (do they respond to my bids for connection?)

- Emotionally Engaged (are they able to understand my emotional needs in these moments and create a shared sense of safety?)

If we can create this emotional safety, then both parties will know and trust that they exist in the other’s mind. This implicit sense of being held in mind is what Winnicott described as the ‘internal holding environment’; something that evolves out of the literal maternal holding environment throughout childhood, as the child develops an internal working model of relationships.

In a secure relationship we can have our independence, knowing that our partners won’t forget about us or withdraw their love in our absence. In an anxious relationship, we cannot be so sure. ‘O what a joy it is to hide,’ wrote Winnicott, ‘And what a disaster to never be found.’